Zabriskie House

Built in 1904, Restored in 2019

Located in the heart of Aurora, Zabriskie House’s broad, columned front porch overlooks picturesque Main Street and one of Aurora’s grand Gingko trees.

Featuring twelve guest rooms, a double parlor with cozy fireplaces, a wood-paneled dining room for private events, a stunning three-story grand staircase, and a remarkable collection of original contemporary art, Zabriskie House serves an ideal gathering spot on warm summer evenings and crisp autumn nights.

Zabriskie House is best enjoyed in the company of other adults. Please note that we do not accommodate children under the age of 12 without a private residence rental.

Included in Your Stay

- Concierge support

- Fire pit & s'mores

- Parlors with fireplaces & games

- Access to the activities calendar

- Coffee & homemade granola bars

- Access to the fitness center

- Access to the nature trail

- Glass of wine each afternoon

Private Residence Rentals

With the rental of all 12 guest rooms at Zabriskie House, you may hold private dinners and events at the home. View our private rental packages to learn more and contact us for pricing and availability.

History of Zabriskie House

This stately home was built for E.B. Morgan’s grandson, Robert Morgan Zabriskie, in 1904. After pursuing an education at Princeton, Robert returned to Aurora with his wife, where he soon became president of Wells College and dedicated decades of service to Aurora.

1833 Kitchen & Bar

Inside the Aurora Inn, 1833 Kitchen & Bar offers creative, locally-sourced breakfasts, lunches, and dinners in its cozy dining room and on its expansive lakeside veranda.

Learn More

Archery

Join our experienced guides and learn the basics of archery using a traditional recurve bow.

Learn More

Aurora Cooks!

From tasting experiences and show-stopping dinners, each session at Aurora Cooks! will inspire your creativity, expand your culinary knowledge, and create memories with your loved ones.

Learn More

Aurora Inn

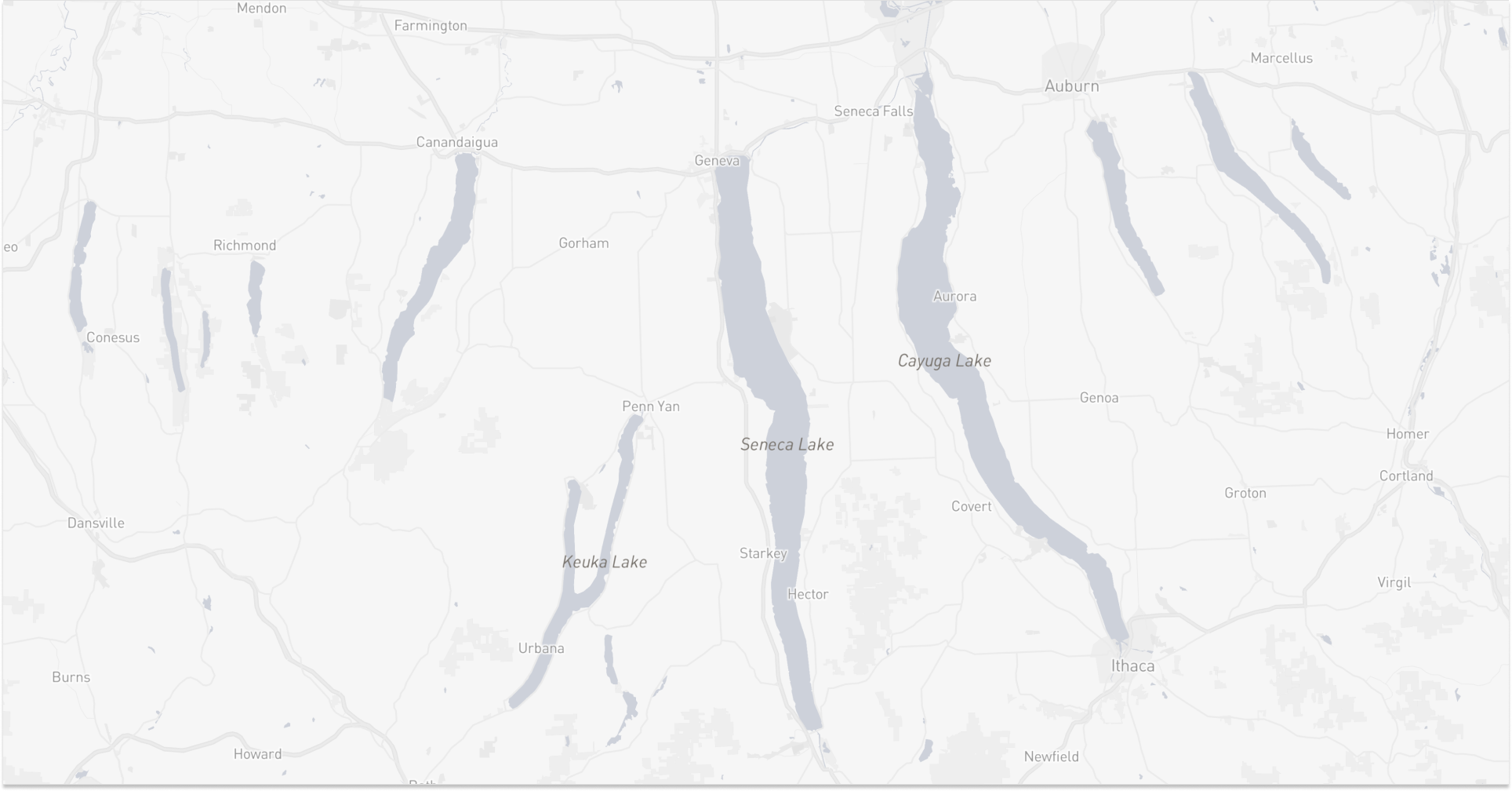

Positioned in the heart of the village on the shores of Cayuga Lake, the Aurora Inn and its ten guest rooms are the flagship centerpiece of the Inns of Aurora.

Bicycles

Whether you’re taking a casual ride down Main Street or cycling through the scenic country roads that surround Aurora, our fleet of bicycles is sure to help you get out and explore!

Learn More

E.B. Morgan House

This dramatic yet intimate lakefront mansion combines cheerful décor with historic grandeur in its seven guest rooms.

Learn More

Fargo Bar & Grill

Creative pub fare and local brews are the calling card of the Fargo Bar & Grill. Enjoy a flight of local craft beer, relax on the shady patio, or stop by for a round of pool or darts.

Learn More

Guest Arrivals

All Inns of Aurora guests are welcomed to check in at our centralized welcome cottage, Guest Arrivals.

Learn More

Lakeside Tent

Our Lakeside Tent is a dynamic space for gatherings of up to 200 guests in the warmer months of the year. Enjoy lake views and a relaxed yet refined Finger Lakes atmosphere.

Learn More

Nature Trail

Our 3.5-mile nature trail provides a compelling way to experience the landscape surrounding Aurora, whether you journey out on your own or sign up for a guided hike with our outdoorsmen.

Trail Map

Orchard Cottage

Tucked along Aurora’s quiet back lane, Orchard Cottage retains the charm of its 1850s character while thoroughly modernized as a restorative, private retreat.

Learn More

Rowland House

Spacious lakefront lawns meet refined worldly style in the expansive, relaxed Rowland House and its ten chic guest rooms.

Learn More

Rowland House Boardroom

With a private residence rental of Rowland House, enjoy the use of the home’s executive boardroom for strategy sessions for up to 15 guests.

Learn More

The Spa Café

The café is open exclusively to Spa guests and is the ideal spot to nourish your body throughout your visit. Our complimentary grazing table provides salads, soup, and light fare.

Learn More

Taylor House

Situated in the heart of Aurora,Taylor House was built in 1838 as a grand lakeside estate. Today, it has been meticulously restored and reimagined as sophisticated event and meeting center.

Learn More

The Farmhouse

With ten guest rooms, the Farmhouse offers a tranquil retreat in a farm-inspired setting. The Farmhouse will open in January 2026.

Learn More

The Loft

With historic hand-hewn beams, exposed brick walls, and natural light from windows on three walls, the Loft is an inspired destination for gatherings of up to 50 guests.

Learn More

The Schoolhouse

The hub of activities in Aurora, the Schoolhouse is the home to the Fitness Center, the Loft, and Basecamp Adventure Center.

Activities Overview

The Spa

Situated on the crest of the hill above Aurora with stunning views of Cayuga Lake, our farm-inspired Finger Lakes spa campus promotes healing and harmony in your body and mind.

Learn More

Village Market

In the heart of Aurora, the Village Market offers a selection of gifts, freshly brewed coffee, pastries and desserts, and craft beer. This quaint market also features take-home meals and snacks.

Learn More

Wallcourt Hall

This boutique hotel offers bold design and vibrant art throughout its 17 comfortable guest rooms.

Learn More

Waterfront

Just north of Rowland House, you’ll find our guests-only waterfront access. Launch a kayak, canoe, or paddleboard, step into Cayuga Lake from our shore, or simply relax and enjoy the view. Watercraft are available seasonally.

Learn More

Zabriskie House

Serene hues and contemporary details transform this stately home and its ten guest rooms into a refreshing retreat.

Learn More

Our Guests Say it Best